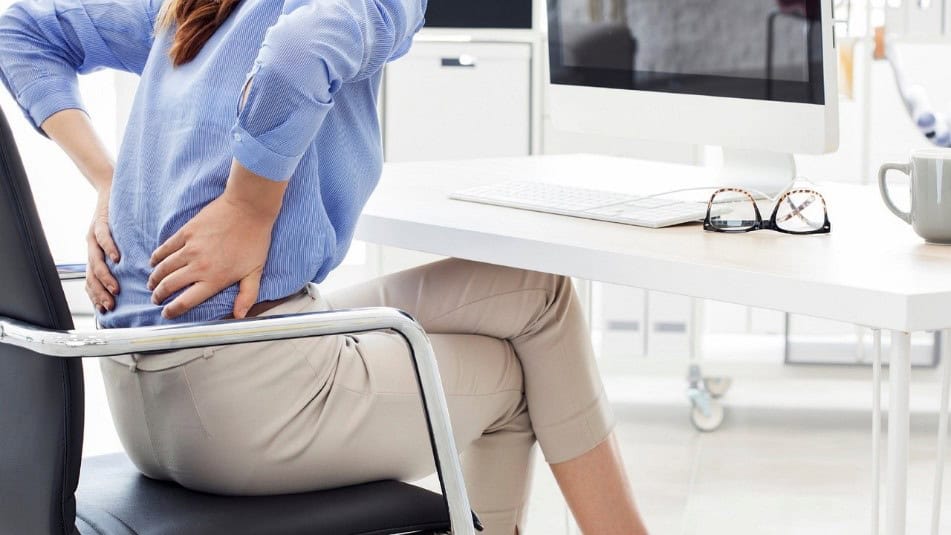

An estimated 60-90% of adults will experience lower back pain at some point in their lives. The risk is notably higher among males and those involved in manual labour and repetitive tasks. The surge in remote work has contributed to the global problem of back pain, as it often involves prolonged periods of sitting, reduced physical activity, and easy access to snacks, which contributes to weight gain and muscle loss.

This decrease in muscle strength increases the likelihood of experiencing back injuries. Lower back pain may appear after running, standing for extended periods, deadlifting, or engaging in other strenuous activities. Additionally, extended periods of sitting put extra pressure on the lower spine, further elevating the chances of developing back pain.

Etiology and Risk Factors

Lower back pain (LBP) has a diverse etiology that includes different conditions such as mechanical, degenerative, traumatic, metabolic, neoplastic, and congenital, each requiring a different therapeutic approach. LBP risk factors are also varied, including occupational, lifestyle choices, hereditary predisposition, and psychological, social, and economic factors. Yet lower back pain may become chronic and long-term as it is influenced by psychological, physical activities, and social-economic factors as well. Almost everyone will experience LBP at some point in their life. Usually, back pain is confined to the lumbar region, associated with fatigue, inability to stay in one position for long, and a general inability to engage in everyday activities. Few people have chronic incapacitating low and lower back pain, which influences social, occupational, and mental lifestyle. It is clear that aging increases the likelihood of back pain, but the pain can occur even in children or teens.

Age is an important risk factor, while the most apparent one is obesity, characterized as BMI > 30. Excess weight can stress the lower back. Some individuals tend to gain weight in the stomach, making them more prone to back pain. Obesity also increases the risk of other diseases in the musculoskeletal system, spine, lumbar region, and spinal cord. Obesity increases the risk of LBP, as do other risk factors. Diseases of the cardiovascular system and diabetes are also more likely to occur in obese patients, and diabetic illnesses contribute to muscular-skeletal, spinal, and paraspinal pain. Medium physical fitness or poor physical fitness is also a risk factor for developing low and lower back pain. It has been shown that people who have strong back muscles can lessen the risk of developing back pain. Regular strength exercises can increase muscle power, and regular activities can include walking, jogging, and exploring the outdoors. Knowing personal lower back pain risks can help prevent it in the first place and manage it if it occurs. This is because LBP is thought to be a multifactorial or multi-causal condition with physical, emotional, and socio-economic contributors. Therefore, creating an intervention for people with different influences and differences can help mitigate the risk for LBP or facilitate early and chronic disease management. The efficacy of medical interventions does vary from person to person, influenced by personal factors such as weight, size, sex, and cultural background; thus, medical research must utilize a comprehensive as well as a multifactorial approach, rather than a reductionist one, in the management, research, and support for the prevention of BPS.

The causes of back pain can be categorized as either injury-related or non-injury-related. Injury-induced back pain stems from accidents such as motor vehicle collisions or falls. In other cases, back pain emerges without a specific accident. Mundane actions like reaching for an object, bending to pick something up, or even sneezing can trigger atraumatic back pain. In certain cases, infections or spinal tumors may cause back pain, particularly if this pain accompanied by unexplained weight loss or fever. Fortunately, preventive measures and self-care strategies can alleviate most back pain instances, particularly for individuals under 60 years of age. If prevention falls short, you can always consult an orthopaedic surgeon for proper diagnosis and treatment.

(https://www.flickr.com/photos/152511098@N08/33348393655)

Symptoms related to back pain can vary widely and may be indicative of underlying. Understanding these symptoms is crucial for timely diagnosis and appropriate treatment. Here are some common symptoms associated with back pain:

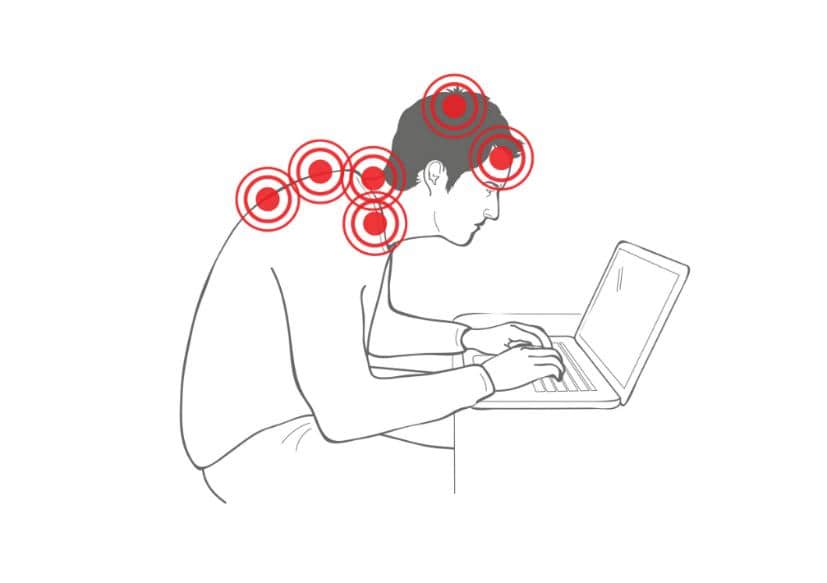

Poor posture can lead to back pain even at a young age. Incorrect posture places stress on muscles, spinal joints, and discs, which can accumulate and weaken these structures over time. Prolonged hunching while standing or sitting strains back and core muscles, leading to stiffness and weakness. When exercising, be sure to avoid incorrect lifting techniques which can result in lumbar disc herniation and radiating pain. Even working on a laptop while lying on the belly can negatively impact the lower spine. It’s important to note that maintaining correct posture will benefit you in the long run.

(https://pixabay.com/sk/photos/boles%C5%A5-chrbta-boles%C5%A5-tela-ergon%C3%B3mia-6949392/)

Here are tips for handling back pain and maintaining activity:

To prevent back pain, it’s crucial to maintain good posture while sitting and standing and incorporate regular exercises that strengthen your core muscles. Here are some tips to prevent back pain:

(https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Technology_stress_hunch.png)

To diagnose and address your back pain, the process begins with a thorough medical interview and examination to understand your symptoms and potential causes. You may also undergo back X-rays or MRI scans to pinpoint the source of the pain. After gathering this information, your orthopaedic surgeon will provide you with a diagnosis and discuss treatment options.

A range of treatment options, split into conservative and invasive management, are utilized in the practical management of low back pain (LBP). We encourage an early discussion with a doctor, physiotherapist, or other healthcare professional if you are experiencing LBP, as the most commonly indicated therapies are quite simple and can be initiated almost immediately. There is no one-size-fits-all policy for treatment, and the therapies that work best for each person also differ. It is probable that one might respond better to a given therapy than another; hence, a multi-professional approach is often recommended. Conventional treatment choices may involve:

– Medication

– Physiotherapy

– Psychologically informed treatment

– Injections

When conservative management fails, patients face a number of different surgical options. These may include:

– Artificial disc replacement

– Facet joint surgery

– Lumbar decompression surgery

– Lumbar fusion surgery, including minimally invasive surgery

– Sacroiliac joint fusion surgery

– Scoliosis surgery

It is vital that patients are active agents in decision-making when it comes to shared decision-making, and understanding both the likely outcomes and potential risks of any proposed procedure is important. Regularly reviewing these aspects is crucial, as interventions can have a large impact on patients’ perceptions of LBP and their rehabilitation. Management of chronic LBP is very rarely about simply seeking pain relief but rather facilitating a return to activity, and for some, it involves enhancing well-being even when pain persists. Based on the numerous inferences made in this review, we suggest a proposed treatment protocol.

Medication

One of the goals of the treatment of patients with neuropathic and nociceptive pain, as part of a comprehensive approach, is pain relief. Pain can be mediated in the central and peripheral nervous systems via the use of various medications. Medication can be used to prevent, relieve, or reduce pain. Medications can be used for singular or combination therapies on both healthy and damaged areas of the human body. Even though the use of medication presents a symptomatic treatment, the improved pain relief enables an improved early exercise response and return to work. A pain model that uses medication as a recovery medium has been proposed. The combination of both therapies is the ultimate treatment.

The treatment of lower back pain often commences with prescribed oral medication, depending upon the pain intensity and/or duration, back pain diagnosis, musculature dysfunction and/or pathology, and lower back pain presentation (with or without leg pain). Medication may also be used as an adjunct to other treatment therapies. A reduction in the pain score or pain level, as well as a secondary decrease in the reduction of pain behaviors in the short term and long term, would be expected. The health professional usually prescribes a lower dose for the shortest amount of time in order to decrease the risk of side effects. Medication can be used to help manage or cope with lower back pain, but in contrast to active treatment therapies, medication should not increase pain and/or symptoms. Lengthy medication use, as part of a routine monitoring follow-up treatment for lower back pain by the health professional, is recommended, irrespective of the treatment effect. Often, medications do not work in all people and are no better than placebo medication in relation to patients returning to bed or work loss. Medication treatment trends are changing, with increases in non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and paracetamol. Commonly prescribed back pain medications include: anti-inflammatory drugs, analgesics, muscle relaxants, corticosteroids, anti-epileptic drugs, anti-depressants, opioids, or injected nerve block analgesics. Counseling, healthy eating, and sleep hygiene practices may also be recommended by the health professional to help with the treatment of lower back pain. Medications need to be monitored by the health professional for side effects or under medications, especially if multiple medications are prescribed.

Physiotherapy

Physiotherapy includes a range of hands-on and exercise rehabilitation techniques to improve body mechanics, muscular strength, endurance, and flexibility, which in turn will facilitate activities of daily living and reduce the potential triggers of back pain. Physiotherapy incorporates a range of assessment and treatment techniques that can be tailored to the individual’s demonstrated need. These include but are not limited to:

– Manual therapy

– Trigger point release

– Stretching and yoga-based exercises

– McKenzie-based subjective and objective testing and therapy

– Strengthening

– Education on posture and body mechanics

Surgical Interventions

When conservative therapies fail, surgical intervention can be considered for lower back pain. Historically, surgery was used as a last resort due to its invasiveness and high rate of surgical complications. Nonsurgical techniques should be exhausted prior to considering surgical interventions. Patients who are candidates for surgical intervention have failed conservative therapy and present with an underlying organic pathology. Psychological testing does not appear to provide an advantage for surgical success. There is good evidence that patients with spondylolisthesis and neurogenic claudication or radiculopathy may benefit from surgery. On the other hand, the literature is equivocal on the benefit of surgery for patients with degenerative disc disease.

It is important to note that surgical complications could result in a patient’s preoperative disability status being worse than their preoperative functional status. The goals of lower back surgery should be to improve quality of life and function. Innovative methods are being used with anterior spine techniques. The use of minimally invasive spine techniques is only for those patients who do not have central canal stenosis but have disabling back and/or leg pain. Each patient who is decided to undergo a surgical procedure must be extensively evaluated preoperatively and postoperatively. With the increasing satisfaction of patients who have undergone anterior spine surgery, there is a new level of maturation among surgical colleagues who treat anterior spine patients. The most important goal is informed consent. This requires patients to have intimate discussions with their surgeons. A complete understanding of the procedure and its risks should be discussed in great detail. The spirit of informed consent embodies that the decision for anterior spine surgery is ambitious, but with the discussion between the patient and the physician, the risks are worth the potential short-term gains and the repercussions of the decision.

(https://www.pexels.com/photo/photo-of-woman-in-a-yoga-position-4057839/)

Differentiating between a regular back strain and a serious lower back injury depends on the duration and intensity of symptoms. Mild to moderate discomfort that responds well to rest and self-care is typical of a common back strain, whereas severe and persistent pain, along with leg numbness or weakness, may signal a potentially serious lower back injury that warrants immediate medical attention.

If you experience sudden lower back pain after prolonged standing, it’s advisable to rest, apply ice or heat, and consider over-the-counter pain relievers, but if the pain persists or worsens, consult a healthcare professional for a proper evaluation.

It depends on the severity of the pain and the patient’s condition. For mild cases, it’s possible to achieve complete recovery from lower back pain without medications or surgery through a combination of physical therapy, lifestyle adjustments, and exercises. It is best to consult an orthopaedic surgeon for this.

To prevent further injury when performing deadlifts or other exercises at the gym, ensure proper form, engage your core muscles, lift with your legs, and start with a manageable weight. Do not overexert yourself.

Good posture is crucial in managing chronic back pain as it helps reduce stress on the spine, muscles, and ligaments, which can alleviate pain and prevent worsening of the condition.

Dr Yong Ren graduated from the National University of Singapore’s Medical faculty and embarked on his orthopaedic career soon after. Upon completion of his training locally, he served briefly as an orthopaedic trauma surgeon in Khoo Teck Puat hospital before embarking on sub-specialty training in Switzerland at the famed Inselspital in Bern.

He underwent sub-specialty training in pelvic and spinal surgery, and upon his return to Singapore served as head of the orthopaedic trauma team till 2019. He continues to serve as Visiting Consultant to Khoo Teck Puat Hospital.

Well versed in a variety of orthopaedic surgeries, he also served as a member of the country council for the local branch of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Osteosynthesefragen (Trauma) in Singapore. He was also involved in the training of many of the young doctors in Singapore and was appointed as an Assistant Professor by the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine. Prior to his entry into the private sector, he also served as core faculty for orthopaedic resident training by the National Healthcare Group.

Dr Yong Ren brings to the table his years of experience as a teacher and trainer in orthopaedic surgery. With his expertise in minimally invasive fracture surgery, pelvic reconstructive surgery, hip and knee surgery as well as spinal surgery, he is uniquely equipped with the tools and expertise necessary to help you on your road to recovery.